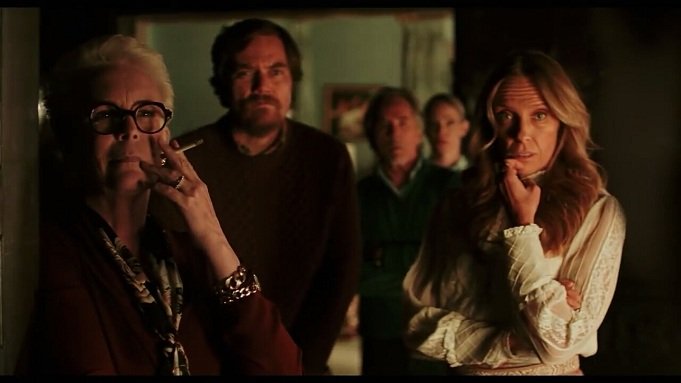

The hunting knives listed here made the cut, as it were, because they were revolutionary in their time or because they worked so well that they influenced knife design thereafter. Directed by Rian Johnson. With Daniel Craig, Chris Evans, Ana de Armas, Jamie Lee Curtis. A detective investigates the death of a patriarch of an eccentric, combative family. Offizieller 'Knives Out: Mord ist Familiensache' Trailer Deutsch German 2020 Abonnieren (OT: Knives Out) Movie Trailer Kinostart: 2. Knives Out is a great antidote to the Oscar contenders and family fare that dominate this time of year. It's a purely fun time at the movies thanks to its strong story and fantastic performances.

The best hunting knife is a knife that can gut, skin, possibly butcher, and possibly cape whatever unfortunate animal got in the way of your bullet. The knife must also be able to do a wide variety of odd jobs such as whittling fuzz sticks, chopping poles for a stretcher, cutting a switch for a lazy horse, and chopping onions in camp. Although butcher knives work best for butchering, and scalpels are preferred for caping, and just about anything can work on any job if you’re skillful enough, some designs simply work better than others.

The blades listed here made our cut, as it were, for the best knives for hunting, because they were revolutionary in their time or because they worked so well that they influenced knife design thereafter. There are only five of them, because only five truly deserve the designation “best hunting knife ever.”

Marble’s Ideal Hunting Knife—One of the First High End Hunting Knives

Once upon a time, there was no such thing as a hunting knife. If you hunted, you did it to feed your face, and not for sport, and if you needed a knife you stole one from a kitchen, or bought a butcher knife and made a sheath for it. But then the idea of hunting as recreation caught on, and in 1898, a Michigander named Webster Marble hit on the idea of a dedicated knife for this new breed of outdoorsman. He called his new knife the Ideal model.

The Ideal had a 6-inch clip-point blade made of good steel with a wide fuller, or groove, to save weight. Marble added a stacked-leather or stag handle, aluminum pommel, double brass crossguard, and asked a list price of $1.25. The sheaths were pretty wretched, but that didn’t stop anyone. Whatever the job, the Ideal would do it, and the knife was in production from 1899 to 1974.

Reintroduced in 2007, the Ideal is now a high-grade knife with a blade of A2 steel, all sorts of handle options, and a list price that can go over $300. Chromium for mac браузер. That’s because now, in its third century, the Ideal is still ideal, and if you have a job to do, it will do it.

Want the Sharpest Hunting Knife? Try the D.H. Russell Canadian Belt Knife

One of the most imitated knife designs of all time (at least 16 companies are copying it), this is the brainchild of a Canadian cutlery-store owner named Dean Russell. To produce his knife, in 1958, Russell chose Grohmann Knives in Pictou, Nova Scotia, and they have produced it ever since. The Canadian Belt Knife has an elliptical blade and a distinctive offset handle that was originally made of rosewood and is now available in stag as well.

In use, the RCBK is as close to a scalpel as you are going to find. You can hold it in any position, control it to a fare-thee-well, and you’ll see that it’s one of the very few designs that is equally capable at gutting, skinning, and caping. Warren Page, who was forever taking animals apart, had one and doted on it.

Grohmann makes the RCBK in stainless- and tool-steel models. I detest the former; I’ve never been able to get one sharp. The tool-steel knives take an edge just fine. Grohmann now makes all sorts of variations on this theme, but what you want is the #1 Original Design. It’s a tool of astonishing versatility, a design of authentic genius.

Looking for the Best All Around Hunting Knife? Behold, the Randall Model 3

In 1936, a young Florida outdoorsman named Walter Doane “Bo” Randall watched a boat hull being scraped with an unusual-looking hunting knife. He bought it on the spot, tracked down its maker—an eccentric Michigander named William Scagel—and asked him how to make knives. Scagel told him, and in 1937 Randall made his first knife for sale. Today, 82 years and thousands and thousands of knives later, Randall Made Knives in Orlando, Florida, has never caught up with its orders.

Randall produces several dozen designs, but the Model 3, which is billed as its heavy-duty all purpose outdoor knife, is not only the first model, but the most popular. It is one of the most copied knives in the world. Every custom smith either began by imitating the Model 3 or currently does and calls it by another name.

Aside from its fit and finish, which are infinitely better than they used to be, the Model 3 has changed very little over the years. Randall began by using automobile leaf springs for blades, but soon switched to Swedish-made 01 tool steel, and that’s still what they use. The stacked-leather handle is still standard, although there are all sorts of options available, and the stainless-steel dome nut, which used to hold the handle in place, has been replaced by one that fits flush with the buttcap.

A Randall will not hold its edge forever and ever. Bo thought it best to make something that could be re-sharpened easily. If you know how, you can get a razor-like edge on a Randall. The first one I ever bought, in 1957, nearly took my finger off in the first five minutes I owned it. I fell desperately in love.

Want the Best Steel for a Hunting Knife? Get a Diamond Blade Summit

The Summit looks like a modest-sized, well-thought-out hunting knife, and not much more. The blade is ground from D2 steel, which was designed for die-making, has a lot of chrome in it, and is noted for its toughness and edge-holding ability. Lots of makers use D2. What sets the Summit, and all Diamond Blade knives apart, is what happens to that D2 blank on its way to becoming a blade.

This brings us to nuclear submarines. The way you build a nuclear sub is to make the hull in sections, stuff in all the neat machinery and electronics, then weld the sections together. Those welds need to be very strong, for obvious reasons. And for this the shipyards use a machine whose business end looks like the rolling ball on a deodorant bottle. As it passes over the steel of the hull sections, it subjects them to enormous heat and pressure, fusing them together forever.

In 2003, Charles Allen, who runs DiamondBlade, got together with metallurgists from Brigham Young University to see if this technique could be adopted to knife blades. It could, and it became known as Friction Forging. It results in a blade whose edge is off-the-charts hard at Rc 65-69, while the spines are Rc 40.

Where conventional forging rearranges steel down to the molecular level, Friction Forging works at the subatomic level. So what you get is a blade that is almost impossible to dull, is not hard to re-sharpen, and can be bent double and bent straight again without breaking. I’ve spoken to elk guides who have field-dressed three of the awful mud-caked beasts with a DiamondBlade and never so much as touched up the edge. For a conventional knife this is unthinkable.

No one else is doing what DiamondBlade does. There are other knives that will take as sharp an edge, but nothing will hold it nearly as long. Your hand will give out long before the blade does.

Want a Perfect Drop Point Hunting Knife? Consider the Loveless Drop Point

Now here is a tale: In December, 1953, a young Merchant Seaman named Robert Waldorf Loveless went into Abericrombie & Fitch in New York City to buy a Randall knife. When told that there was a nine-month wait, he did what anyone would do and went to a junkyard in Newark, New Jersey, where he found a leaf spring from a 1937 Packard, forged it into a blade on his ship’s galley stove, and then took the finished knife back to A&F, who said, “Make more. We’ll sell them.”

Knives Out German Stream Free

Loveless did. Between 1954 and 1960, he made around a thousand knives, essentially Randall copies, that sold under the name Delaware Maid. They outsold Randalls, and today if you happen across one, you’re looking at somewhere between $7,000 and twice that.

Then in 1972, Loveless introduced the knife that would bring him immortality. It was called the Drop Point Hunter, or simply the Drop Point, so called because the point was ground down below the spine, and when you held the knife upside down to gut an animal, the point stayed clear of the guts.

The Drop Point is the embodiment of form following function. It is a minimalist masterpiece. The 3.5-inch blade was deeply hollow ground and made of an exotic semi-stainless steel called 154-CM that no one had used for knives before. Loveless tapered the tang down to 1/16-inch, which put the balance of the knife right at the hilt. He passed up the narrow-tang handles Randall used and went to full tangs because epoxy was now available and could hold a stag or micarta scale in place forever.

He etched his trademark rather than stamp it, because he believed that stamping weakened the blade. His hunting-knife sheaths had no snaps, because he didn’t believe snaps could be counted on. The list goes on and on.

Knives Out German Streaming

Loveless was a showman and a personality, and his knives, good as they were, soon commanded prices all out of proportion to their value. As Loveless himself put it, his $250 knives sold for $650, and the extra $400 was the price of his trademark on the blade. He was also an uneven workman. There are Loveless knives that are jewel-like in their fit and finish, and some that cause you to wonder how they got out of the shop.

So be it. Loveless is probably the most-imitated knifemaker of all, exceeding even Randall. This is fortunate, because if you can’t afford the $4,000-$5,000 price of the real thing, there are plenty of excellent copies that cost a lot less.

MORE TO READ